|

CHAPTER

18: Traditional Livelihoods of Rural

Peoples (de Blij & Murphy)

1)

Primary Activities

– the extractive sector; direct extraction of natural resources from the

environment; hunting and gathering, herding, fishing, mining, lumbering,…

2)

Secondary Activities

– the manufacturing sector; processes raw materials and transforms them into

finished industrial products; production of an almost infinite range of

commodities (toys, chemicals, buildings, …)

3)

Tertiary Activities

– the service sector; engaged in services; transportation, banking, education,

…)

4)

Quaternary –

concerned w/ collection, processing, and manipulation of information &

capital (finance, administration, insurance, legal services)

5)

Quinary – require a

high level of specialized knowledge or skill (scientific research, high-level

management)

1)

Agriculture – the deliberate tending of crops and livestock in order to

produce food and fiber.

2)

Before farming – a recent innovation (12,000 yrs.), hunting and

gathering – have been forced into more difficult environments; agriculture

permitted people to settle permanently with the assurance food would be

available (storage)

3)

Before farming: early

communities improved tools (sticks, baskets), weapons (clubs, spears),

innovations (fire)

a)

Metallurgy: separating

metal from ores, developed prior to plant & animal domestication

b)

Fishing – after Ice Age

(12,000 – 15,000 yrs ago), coastal regions become warmer

c)

Alternating periods of

plenty and scarcity

4)

1st

Agricultural Revolution: 12,000 yrs ago (Neolithic Era)

a)

Accompanied by a modest

population explosion

b)

Domestication – animal

(about 40 species today) occurred after people became more sedentary

5)

Subsistence farming:

self-sufficient, small scale, low technology; food production for local

consumption, not for trade (Central & South America, Subsaharan Africa, S.E.

Asia)

a)

Some are confined to

small fields; very likely they do not own the soil they till

b)

Can promote cohesiveness

w/in society, share land, food surpluses, personal wealth is restricted;

cultivators are poor – but free

c)

Shifting Cultivation –

(slash & burn) Cultivation where tropical forests are removed by cutting

& burning, ash contributes to soil fertility; clearings are usually

abandoned after a few years for newly cleared land (150-200 million people)

6)

2nd

Agricultural Revolution: began at end of Middle Ages, benefited from Industrial

Revolution, improved methods of cultivation, harvesting, and storage

7)

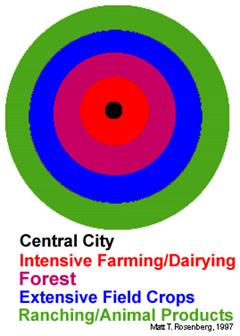

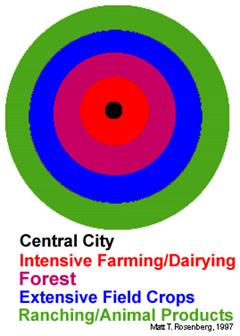

Johann Heinrich von Thünen’s

(1783-1850) Spatial Model of Farming

a)

Witnessed the 2nd

Agricultural Revolution firsthand (in

b)

Concentric rings formed,

within which particular commodities or crops dominated, and others were replaced

(without any visible change in terrain, soil, or climate)

c)

Closest to town –

perishable items, high priced (dairy, strawberries)

d)

Next ring – less

perishable, bulkier crops (wheat, grains)

e)

Outer

ring – livestock, ranching

f)

Von Thünen’s model

assumes: 1) flat terrain, 2) soils and conditions are constant, 3) no barriers

to transportation to market

8)

Third Agricultural

Revolution (Green Revolution), still in progress (began in 1960’s)

a)

Based on higher yielding

strains using genetic engineering

b)

Will the Green Revolution

eliminate world hunger, or will human population use up the benefits?

Argument for both sides…

CHAPTER

19: Rural Settlement Forms

Attributes

1)

Form – influenced by culture, environment,…

2)

Function – impression of social and economic needs (eg. livestock under same

roof as people in

3)

Materials – reflect local availability (not as important as it was in the

past: why?) and purpose

4)

Spacing – relationship between density of houses and intensity of crop

cultivation

a)

Dispersed settlement – houses lie far apart from each other (eg. US

b)

Nucleated (agglomerated) settlement – compact, closely packed settlement

sharply demarcated from adjoining farmlands (eg. Java; most prevalent

residential pattern in rural areas, land use is just as intense)

The

first topic in Chapter V of the summary outline, the development and diffusion

of agriculture, is covered well in most human geography textbooks. Most

textbooks follow the presentations of economic land agricultural activity that

is based on the notions of the nineteenth-century geographer Edward Hahn that

were modified and further articulated in the

Neolithic Agricultural Revolution

There

are major events in the history of the world that are quite transforming; the

invention of agriculture in the Neolithic times was one of those events. The

invention of agriculture enabled the human population to differentiate itself

from the higher primates. By applying agricultural technologies in very simple

forms, humans were able to increase the carrying capacity of the earth's surface

by many, many times. Every culture on the surface of the earth engages in

agriculture in some form. We obviously need food to eat, and cultures have

developed practices for storing food until times of shortage and for moving food

from areas of high productivity to areas of high consumption.

In

addition to the circulation of food, other aspects of food production attract

the attention of human geographers. The spatial patterns of the dietary laws

that govern consumption and production of crops and animals around the world

have fascinated many geographers. Carl Sauer's seminal work, the Agricultural

Origins and Dispersals, published by the American Geographical

Society in 1952, is the springboard for all contemporary geographical

discussions about the origins of agriculture. Sauer believed there were eleven

separate centers of plant and animal domestication. This great invention

probably occurred first in the areas of the tropical seashores where settled

fishermen were able to produce enough surplus so that they could invest some of

their wealth and time into the experimentation and nurturing of plants and

animals. Sauer and others argue that large herd animals may have been

domesticated first for ceremonies and then later used for other purposes. They

conclude this because the religious personages in the early agricultural

communities had the time to rear young herd animals to the stage at which they

could actually participate in religious ceremonies. But of course, no one really

knows for sure. The movement of humans around the surface of the earth diffused

plants and animals to nearly every possible environment. Some of the movements

are well documented; others are only vaguely understood.

Evolution

of Energy Sources and Technology

The

increasing availability of animal energy expanded humans' ability to till the

soil. Techniques of harnessing animals evolved from the early forms of

tying plows to the heavy horns of cattle to the advanced harnessing system for

horses. Europeans developed the heavy horse collar which enabled the weight that

the animals were pulling to be transferred to their powerful shoulders and away

from their windpipe and neck. This made the horse much more effective. The use

of large draft horses enabled farmers to till heavier, more productive soils,

which ensured better yields of grain. Better yields meant more food for animals

and eventually large, more powerful animals. Although agricultural technology

evolved in all parts of the world, the process was slow. Farmers were reluctant

to experiment with new, risky ventures for fear of crop failure and famine.

Regions

of plant and animal domestication

All

the popular textbooks and atlases have maps and charts that portray the assumed

regions of plant domestication. These maps are important because they illustrate

the areas where the wild ancestors of modern crops might be found. The genetic

material in the world of our ancestors is considered precious, because it is

essential for creating new varieties of domesticated plants.

Agricultural Systems Associated with Major Bio-Climatic Zones

There

are two things that must be considered when teaching the contemporary regional

patterns of agricultural production. One is the relationship between agriculture

systems and the climatic zones, and the second is the complicated set linkages

among the production areas and the consumption areas. All forms of economic

activity are involved in the shift of agriculture products to food.

Most

atlases and textbooks contain a version of a map based on the map drawn by

Derwent Whittlesey and published by the Annals

of the Association of American Geographers in1936. Unfortunately, no

agricultural geographer has attempted to modernize this map, and therefore it

must be used with caution. This map attempts to portray the major agricultural

regions in the world. One way to deal with this part of the course is to have

your students study this map making sure they understand the key. The map shows

a pattern of about thirteen varieties of agriculture that reflect environmental

zones. For example, the nomadic herders are found in the arid regions of north

and

What

Whittlesey calls rudimentary

sedentary cultivation really should be thought of as subsistence

agriculture. Another of his categories is intensive

subsistence tillage, one form making heavy use of rice and another

form really using wheat rather than rice. These circulation systems are

essentially the same, but each utilizes a little different crop mixture due to

the climatic differences. Livestock ranching, like nomadic herding and shifting

cultivation, does seem to follow major climatic zones.

If

students look at the map with some fundamental understanding of environmental

zones, they will see very clear patterns. However, this map is only the

beginning, because farmers have greatly modified the environment and even

destroyed major components of it to bring this pattern into reality. The forests

that once covered

Production

and Food Supply — Linkages and Flows

The

concentration of a crop is illustrated by commodity maps in an atlas such as Goode's.

Wheat, for instance, is produced in the central and northern plains of

Maize

or corn, another major crop that is exported, is heavily concentrated in

Rice

is the third major grain that moves in world trade. Enormous concentrations of

rice production occur in south

Other

commodity flows of interest are the movement of coffee and tea from the tropics

to the mid latitudes. Likewise, there is a flow of sugar from the coastal

regions of

Currently,

there is controversy about the flow of food around the world. Many governments

think of food as a strategic material and want to ensure that their local

production is adequate should warfare interrupt the flow of international trade.

In

addition, farmers using their political clout have raised barriers to prevent

the import of food from areas in which food is produced more efficiently. One of

the significant developments in international trade and food in the 1990s has

been the growing resistance in

Land

Use and Location Models

Like

other forms of economic activity, agriculture is influenced by transportation

costs or the friction of distance. The major variable of bio-climatic influences

is modified by the accessibility factor. It has been observed many times that on

areas of seemingly homogeneous landscape, a pattern of land use will have

developed that is dependent upon transportation costs.

The

most fundamental model of that pattern was developed by von Thunen in the

nineteenth century to describe and explain land uses on the north German plain.

The von Thunen model has been described in all the popular textbooks. The

illustration presented here is one of many. The important thing about the von

Thunen model is the way in which it enables students to think about

accessibility and to break free from explanations of agriculture that are based

on out-moded notions of ethnicity and environmental determinism. The model is

particularly useful in explaining the sequence of agriculture that occurred with

the settlement of

Extensive

agriculture at the edge of the von Thunen models or rings involves large land

areas. An average-sized farm in

The

von Thunen Model Explained

The

von Thünen model of agricultural land use was created by farmer and amateur

economist J.H. Von Thünen. His model was created before industrialization and

is based on the following limiting assumptions:

|

In

an

There

are four rings of agricultural activity surrounding the city. Dairying and

intensive farming occur in the ring closest to the city. Since vegetables,

fruit, milk and other dairy products must get to market quickly, they would be

produced close to the city (remember, we don't have refrigerated oxcarts!)

Timber

and firewood would be produced for fuel and building materials in the second

zone. Before industrialization (and coal power), wood was a very important fuel

for heating and cooking. Wood is very heavy and difficult to transport so it is

located as close to the city as possible.

The

third zone consists of extensive fields crops such as grains for bread. Since

grains last longer than dairy products and are much lighter than fuel, reducing

transport costs, they can be located further from the city.

Ranching

is located in the final ring surrounding the central city. Animals can be raised

far from the city because they are self-transporting. Animals can walk to the

central city for sale or for butchering.

Beyond

the fourth ring lies the unoccupied wilderness, which is too great a distance

from the central city for any type of agricultural product.

Even

though the Von Thünen model was created in a time before factories, highways,

and even railroads, it is still an important model in geography. The Von Thünen

model is an excellent illustration of the balance between land cost and

transportation costs. As one gets closer to a city, the price of land increases.

The farmers of the

Settlement

Patterns and Urban-Rural Connection

About

half the world's population still lives in rural regions dominated by

agriculture. The architecture of these settlements varies from place to place,

although it is possible to see broad patterns. The building materials

reflect local conditions as well as the availability of commercially produced

products from elsewhere. There is a relationship between the form of the

architecture and the function that is quite visible in certain areas. Because

most agriculturists live in villages, it is important to view in some detail the

nature of these rural settlement patterns.

Villages

are frequently referred to as nucleated

settlements. This is in contrast to dispersed

settlement, which is the basic pattern that exists in the

Environmental

and Social Impacts of Intensification

Nucleated

settlements, in general,

conform to fundamental cultural features in the landscape. They reflect the

social structure within the village, as well as the local environmental

situation, such as road, dike, or levy along a river. Most frequently, the older

villages were defensive in nature. The houses were close together and surrounded

by some sort of wall Even though the threat of invasion is over in most

places, these villages persist in their compactness and lack of a regular street

pattern.

Geographers

have classified villages according to their shape or form. Linear villages, with

houses lined up along a road are called strassendorfs.

Other villages are described as round

village, a cluster

village or a walled

village. The village pattern was, of course, transferred to the

In

various part of the world, agriculturists built villages using materials that

were at hand. In areas where there was plenty of wood, the houses were

built of wood. Where wood was not available, farmers used various types of

brick. Sun-dried brick, or adobe, is very common in the sunny areas. Fired,

or baked brick, is more common in the areas where the adobe is less

suitable. Houses were also built of stone, and in some locations, poles and

sticks were woven together and plastered over with mud.

The

basic point of all this is that agriculturists were close to the environment and

used whatever materials they had at hand. As transportation improved and

manufactured products could be brought into areas, vernacular styles and

building materials tended to disappear under the pressure of mass production.

The

size and the structure of villages and other forms or rural settlement reflect

the availability of space and local environmental conditions. The North American

farmstead is larger than many villages in

Introduction

to Modern Agriculture

The

second agricultural revolution reached its peak during the hundred and fifty

years from the post Civil War era to 2000. This period saw the development of

barbed wire, various forms of harvesting machines (particularly Cyrus

McCormick's reaper), and the tractor — first with a steam engine and then

with a gasoline engine — which replaced draft animals. The revolution's major

impact was the reduction in the number of people needed to operate farms.

The

third agricultural revolution, beginning approximately about 250 years after the

start of the second, has three distinctive features. The first is the removal of

the lines between agriculture as a primary activity and secondary and tertiary

activities. Farmers and agriculturists now engage in the primary activity of

crop production, some sort of secondary activity of manufacturing or processing

the crops, and tertiary activities of marketing and advertising their products

through co-ops and other marketing organizations. The second distinctive feature

of this agricultural revolution is more intensive mechanization; biotechnology

is the third. Mechanization began replacing animal and human labor in the

The

biotechnological phase began with chemical farming — the substitution of

inorganic fertilizers and manufactured products for manure and humus to increase

soil fertility. Chemicals were also used to control pests, and a wide variety of

herbicides, pesticides, and fungicides have been produced in a never-ending

effort to enhance the yields. This became widespread in the

Food

processing — adding economic value to agriculture products — is the third

part of the revolution, and the part that is achieving (or attracting or

gaining) the most energy and investment. While the first two phases of the

revolution are focused on inputs into the agricultural process, the third is

focused on output. Farmers frequently talk about the third phase as "value

added," and of course it's the third part that involves agriculturists in

secondary and tertiary activities. One of the indications of this has been the

use of the term "agribusiness" in the United States to describe the

blending of old agricultural farm-centered cultures to this new, more integrated

form of production and culture. One of the most significant features of the

third revolution is the elimination of the difference between urban and rural

life styles.

The

industrialization of agriculture in general has caused a number of changes in

agrarian societies. First, there has been change in the application of rural

labor as machines replace or enhance the efficiencies of human labor. In a

sense, the industrialization of agriculture creates surplus labor in the rural

areas that can be used for other urban activities. Second, there is the

development and introduction of new and innovative inputs such as seeds,

chemicals, and different kinds of technologies that supplement or replace

locally produced products. Third, there has been a development of substitutes

for some kinds of agricultural products. Fourth, new uses for agricultural

products have been developed. The conversion of corn to sugar for use in soft

drinks is an example.

Green

Revolution

The

third revolution began in the1960s when a combination of technology was made

available to countries in

It

all began in the mid 1940s when the Rockefeller Foundation of the

The

Green Revolution was based on the development of new higher yielding hybrid seed

varieties, a technology that was developed in the

Consumption,

Nutrition, and Hunger

Despite

the dramatic increase in food supply and reduction in hunger in the world as a

result of the diffusion of Green Revolution technology, there have been numerous

people who have found reasons to criticize this innovation. The division between

rich and poor that existed in the rural areas of the developing countries was

made wider by the Green Revolution. Some observers argue that the economic

conditions that arose from the political power created by the Green Revolution

more than offset the gains that were accomplished in increasing the food supply.

Others argue that the crops produced by with Green Revolution technology are

less nutritious, less flavorful, and less palatable. They also point out that

the fertilizers and chemicals used in the revolution come from fossil fuel, a

nonrenewable resource. Critics also feel that the Green Revolution can increase

erosion and environmental contamination. The need for capital from the West to

implement the changes to infrastructure has put pressure on the economies

to grow more crops for export and take land away from production of crops for

local consumption. It's also pointed out that the Green Revolution focus has

been on rice, corn, and wheat, which are crops that are of particular interest

in

Whatever

the critics say, it is clear the Green Revolution was successful. The countries

in which it was put into place have been able to feed their populations. While

the technology may have created problems, the alternative would be food

shortages and hunger. Neither is a viable alternative.

The

latest revolution in agriculture is being spread about the world from the core

to the periphery through a variety of agencies. First among these agencies are

the international efforts developed by the core nations over the years,

primarily the World Trade Organization (WTO), the European Union (EU), and the

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). These organizations promote the

diffusion of technology, but also support organizations that can usually be

called developmental.

Governments

have for many years regulated the flow of food goods in and out of their

countries to maintain production, consumption, and their own national corporate

profits. This is accomplished primarily by offering either direct or indirect

subsidies to agricultural producers to keep foodstuffs affordable. Over the

years, farmers in the

In

addition to being concerned with their internal food production, core states

have also engaged directly and indirectly in the agricultural sectors of other

nations. Aid for food and agriculture development is widespread and popular

around the world. When the receiving states asked for the aid, the charitable

organizations and the donor states were happy to send it. Many large-scale

agricultural development projects have been initiated around the world, but not

all been successful. One of the lessons learned from attempting to increase food

supply through external aid is that large-scale environmental modification

schemes generally have been unsuccessful. Small-scale projects sensitive to

local, cultural situations and environmental concerns seem to be more successful

over the long run.

Industrial/Commercial

Agriculture

A

useful way to envision the industrialization of agriculture is as a complex

circulation system based on the urban industrial cores. The nature of

agriculture changes and becomes more urbanlike as land devoted to agricultural

activities becomes more tightly connected to the urban industrial cores.

Agriculture has divisions of labor and the farm workers are not self-sufficient.

They buy their food in grocery stores, and get all the inputs from off-farm

sources.

When

thinking about the organization of industrial agriculture, the most important

concept is agribusiness.

This refers to a system of economic and political relationships that organize

food production from the development of the genetic makeup of the seeds to the

retailing and consumption of the agricultural product.

Agribusiness

is organized into flows of political and economic power that are focused on

commodity or food chains. A food chain is usually composed of inputs,

production, outputs, distribution, and consumption. There is an associated

landscape with each of these factors. Many of these commodity or food chains

link a variety of physical environments together. They also link areas of

production and consumption served by manufacturing areas.

In

a sense, agribusiness occurs at a global scale in the same way that a

subsistence village worked in the preindustrial area. In the subsistence

village, forms of production, processing, distribution, and consumption were

organized at the local scale. Occasionally, several villages interacted and

exchanged surpluses. Now, with industrialization and the intense increase in

circulation technology, entire regions of the world are linked together in the

form of production, processing, and consumption.

The

Europeans developed the first global system that linked together food production

in the colonial territories with consumption in the European sector. Early in

the colonial period, a food regime began in which wheat production in the

Environmental

Change — Desertification, Deforestation, etc.

As

we have seen, traditionally there is a correlation between types of agriculture

and bioclimatic zones. The growth of any organism in the plant kingdom is

dependent on water, solar energy, and nutrients from the environment. Therefore

the environment makes a major impact. By harvesting timber and grazing flocks in

the highlands, farmers modified the landscape around the

Perhaps

the most dramatic impacts have occurred on the margins of arid regions where

agriculturists, for a variety of reasons, have expanded into areas that have

thin topsoil and vegetation. Overgrazing and tillage caused a change in the

nature of this landscape that increased the rate of erosion thereby creating

desert-like soils on the surface. The desertification process was accelerated by

short-term climatic fluctuations in some areas, but primarily human activity is

the cause.

It's

a cliché to say that farmers have had more impact on the environment than any

other sector of the economy. Whether this is true or not is impossible to

measure. What is clear is that agribusiness has new ways, using biotechnology,

to modify the environment. Biotechnology refers to the process or the technology

that uses living organisms or parts of organisms to make or modify products, to

improve plants or animals, or to develop microorganisms for specific uses.

Biotechnology is distinct from the Green Revolution because it uses gene

manipulation, tissue cultures, cell fusion, embryo transfer, cloning, and a

variety of techniques unknown to the agriculturists of the 1950s. Biotechnology

has been able to produce what are sometimes called superplants that produce

their own fertilizers and pesticides and are resistant to disease an their

development of microorganisms. Through cloning, it is possible to take tissues

from one plant, insert them in another to form new plant, and produce millions

of identical plants thereby reducing the chances of variation in yields from

particular seeds.

While

the critics talk about cloned material making plants more susceptible to

diseases, elm trees with resistance to the Elm Virus have been successfully

cloned and planted in great numbers in the American Midwest. The debates about

biotechnology certainly are vociferous, and there is really no way for a

geographer to determine which side is going to be correct. It is clear that

biotechnology is a continuation of the industrialization of agriculture. It is

also based in private ownership and capitalism. Biotechnological processes are

patented. Seeds that are patented cannot be grown by the farmers unless they pay

the company that developed them. There are also some notions that if these crops

are exported to the developing world to increase the efficiencies in

agriculture, there will be a social disruption caused by the new seeds. As with

any change, there is no reason to expect its benefits will be equally

distributed. It seems the issue with biotechnology is what are the options of

not exporting these more efficient crops and not using this technology.